A Message from Migrant Workers is a short, animated documentary film developed in collaboration with five Filipino artists who also work as domestic workers in Hong Kong. The narrative presents five personal experiences of migrant domestic workers collated by the collaborating artists.

The collaborative animated film, co-directed by: Cristina Cayat, Jonalyn Molina, Lyn Lopez, Maria Christina Anire & Marichel Tomines (members of Guhit Kulay Hong Kong Filipino Artist Collective) and animated by CG animator Tom McCaughlan aims to shine a light on what it means to work as a domestic worker abroad. Project Coordinator Justyna Kabala talks about the film following its screening in Multicplicity (October 2023)

Q. How did a Message from Migrant Workers come about?

JK: Tom and I worked in Hong Kong between 2017 and 2018, and that’s when we saw how migrant domestic workers would repurpose the city centre on Sundays for community activities. Foreign domestic worker visas only allows workers to live-in with their employers, which means that on their days off most of them choose to spend their free time outside of their workplaces, gathering in public space to relax, meet up, run errands, send parcels home, share food, practice dance, music, or arts and crafts, do sports, etc. These informal collective practices serve as a form of place-making, care, and collective community action – building permanence within temporary conditions. I have made films with worker communities and migrant groups before, but this time we wanted to see if we could find a much more collaborative approach to making films with the community, from research through to dissemination.

Knowing we would like to develop a film project with the community, we were planning to go back to Hong Kong, but then Covid-19 happened, so we had to rethink our approach. In autumn of 2021, we reached out to Guhit Kulay Artist Collective, a group of artists who work as domestic workers in Hong Kong, to see if anyone was interested in taking part in a collaborative filmmaking project. The film was then developed together with the five co-directors from Guhit Kulay: Cristina Cayat, Lyn Lopez, Maria Christina Anire, Jonalyn Molina and Marichel Tomines, in a series of online film-writing workshops, which we conducted on Sundays at the height of pandemic restrictions in late 2021.

Q. Domestic workers are such an integral part of HK with so many stories to tell. Did you know from the start of the project the themes you wanted to highlight?

JK: We knew from the start that we wanted the film to talk about migrant domestic workers’ experience of living and working in Hong Kong, but we wanted the artists from the community to decide what that might mean. The individual themes of the film chapters were selected by the five co-directors through the specific stories from the community that they wanted to highlight. This ranged from experiences of being new to Hong Kong, living and working with employers, working away from families, the effects of the pandemic on mental health, and the importance of community skill share practices and other community-building activities practiced on their day off utilising public space.

Q. What was the collaborative process from having the idea to the finished film?

JK: We wrote a workshop programme, a total of ten sessions, to serve as a skill share activity and a space to generate a narrative for the film. The workshops ranged from learning to conduct interviews, script editing, storyboarding, visual narratives, voice recording and film review sessions. The artists and their contributors from the community engaged in the project with great care and enthusiasm, and as a result we made a longer and more expansive film than we anticipated. The co-directors developed the narrative into five chapters, and although we had an idea of what the visual language will be, what the film has become has exceeded our expectations.

Q. How did you develop the storyboards? What does your storyboard look like?

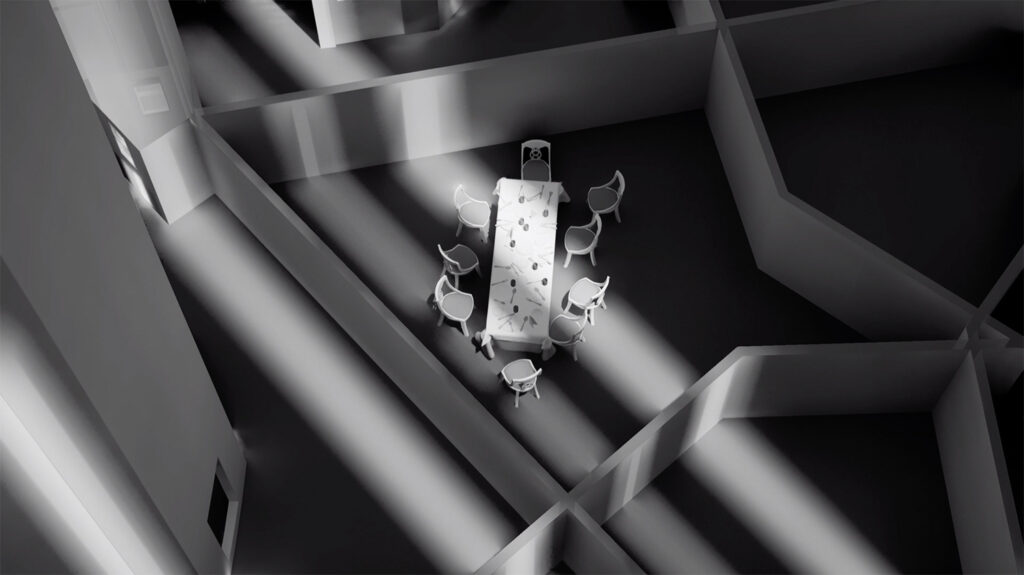

JK: The storyboarding started in the second workshop session alongside the interviewing activities. We asked the artists to bring photographs of specific spaces in the city which were important to the community’s day-off activities. Some of the storyboard was hand-drawn, by the artists, some were photographs, some places were sourced from maps and street view images. The residential architecture scenes were, on the other hand, fictionalised based on the specific stories highlighted through the interviews. In the workshops, we were focusing on sourcing or developing images of environments (interior and exterior), settings and objects which could support the narratives from our interviews. It was amazing to work on the storyboards with a group of artists who love drawing and taking photographs – and this is what really made the visual narrative come together. A lot of the images which made the storyboard are included in the final chapter of the film – a message to migrant workers. Artworks and photographs produced by our co-directors feature in the animated sets, hanging on interior walls, or billboard advertising in the cityscapes.

Q. Why did you choose to use CG animation to illustrate the narrative and environments?

JK: We knew that we wanted to use CG animation – the language of architectural visualisation – to construct cityscapes and landscapes, since the film was to talk about experience of working and living environment. Another reason to use animation was that at the time of the pandemic we were not able to film on location due to local restrictions. Tom, who translated the storyboard to the animated scenes in unreal engine, really made the stories come together through his skilled craftsmanship. Also, the stillness of the deserted architectural environments served almost as backdrops, giving space to the voiceover narratives.

Q. Will you develop this collaborative approach for future filmmaking projects?

JK: I have worked with communities on filmmaking projects before, but this was the first project we’ve worked on fully remotely, transnationally, completely online. As a collaborative model, it worked very well in the time of the pandemic, when everyone was online. I wonder how successful the project would be if we started it now that people can move more freely and enjoy in-person activities. Over the summer, we had many conversations about the project with our co-directors, and all agreed we would prefer an in-person project now.

This project has helped us develop collaborative storytelling methods as an inherently collective endeavour. Working out what shared authorship means in filmmaking practice, as an attempt to challenge the hierarchies traditionally embedded in film production. For me personally it’s the abiding lesson this project has taught me, and something I hope to continue in my filmmaking practice.

Q. You started working on the film back in 2020. What impact has working on the project had on the collaborating artists?

JK: I hope that the project was useful for the film’s co-directors. As practicing artists, they are very active in the community, organising and supporting other migrant workers with skill sharing workshops and art activities, and I believe working on the film has in some ways been an extension of their practices.

The underlying ambition that evolved with the film was to raise awareness and inspire policy change in support of domestic workers, so it was great that we had screenings across Hong Kong and the Philippines. We’ve also received support for our film screenings from Philippines-based Overseas Workers Welfare Administration, higher education institutions, and ethical employment agencies, with screenings involving domestic worker organisations in the panel discussions.

One of this project’s aim was to offer skill share in filmmaking and my hope was that it would perhaps spark an interest for the use of filmmaking in the artists’ creative practices. Looking back at our film and workshop programme, I would like to quote some thoughts of our co-directors from our conversations about the project.

JM: This animation helped me to share my thoughts and my ideas, and to express my point of view. It’s brought me more to collaborating with others and sharing what we learnt from that, it’s expanding the learning we did in the workshops, and then we can share this with others.

I think this project can have a big impact for us because we can say that we are not just domestic helpers, we can prove to others that we can do other things, like art. It can have big impact on us, as a group, after this film, other groups are already contacting us about this film, so yes, for making connections and collaborations again. (Jonalyn Molina)

CC: Before this project I wasn’t really interested; I mean I had some plans about doing some videos of my dresses, but now, it’s like, we can create meaningful documentaries that could be passed on to important government agencies that can protect the workers. Education, for younger generations.

I think this filmmaking is the answer. For a long time, we were looking for venue to express this, to tell people that we need space, we need help, that actually this is happening, and we need this to be shown to people, the academia, the researchers, that maybe it could change, that the impact could be a change in policy for the treatment of migrant workers. (Cristina Cayat)

LL: I think this film is very important. It’s important for everyone. Because some people have no idea about what’s happening to migrant workers. I think everyone should watch this. I think those migrants planning to go somewhere else they should watch this. Because the expectation is not the same. They should watch the film because it will give them courage. They would understand what is happening and how your mindset should be when you go out there. The story will give you courage, and idea on how to cope in every situation, it’s really helpful. And for the employers, they will understand what’s happening and what are the struggles.

Also, the children of the Filipino Overseas workers, they should understand what their parents face in other countries just to give them a better life. We look so happy on our social media posts; it seems there’s no problem at all but behind the posts we are facing so much struggle about our situations. Anxiety and depression are very common part of our everyday life. We want to go home to take care of our children and we need to choose between giving them a better life or be there with them but struggling financially. The biggest decision that we ever made is to leave our children. That was the most painful part. (Lyn Lopez)

MA: I didn’t expect this project to have so much impact on all of us. It brought more opportunities and opened more doors, and some well-known groups started collaborating with us. We got introduced to other people and we did more workshops or art exhibitions with them. It’s like this film gave us more opportunities to express our ideas, showcase our talents, it was eye-opening to others to understand the stories and experiences being migrant workers and knowing our rights, to empower us more, to do more and be productive.

I guess it’s empowering me, this has helped me to go out of my comfort zone, to make more films in the future, to share them and showcase our talents, show that we are not just migrant workers, we are more, and through sharing our work we can empower and inspire others too. (Maria Christina Anire)

Stills from A Message for Migrant Workers. Courtesy of the filmmakers